THE BIG THREE (plus Kedrion):

Here’s a quick summary of 2023 results from the Big Three (CSL, Grifols, and Takeda), as well as Kedrion. Demand for immunoglobulin is predicted to be strong, donor fees and cost-per-liter of collections have come down significantly, and plasma supplies are looking like they will exceed pre-pandemic collection highs.

Forecasts for immunoglobulin demand remain strong

CSL anticipates 6-8% growth in demand for their Ig portfolio, Grifols expects “high single-digit” growth, Takeda is predicting 5-8% growth, while Kedrion did not offer a forecast.

In the last quarterly, I gave my own forecast of closer to 10%. I continue to expect that sort of growth. My expectation is based on a combination of the forecasts given by experts, as well as greater optimism that Europe will soon see more appropriate Ig issues (European use is significantly below what is medically appropriate according to Latent Therapeutic Demand estimates).

Donor fees and cost-per-liter have seen double digit reductions

CSL reports a 14% reduction in donor fees (July 2022 to July 2023); Grifols has seen a 22% reduction in cost per liter (calculated from July 2022); Takeda has seen their donor fees decline by 17% from 2021; Kedrion reports a 22% reduction from July 2022. No one is expecting a return to pre-pandemic fees which were around $30-50 per donation. My expectation is donor fees will stabilize around the $50-75 range over the next several years.

Supply of plasma has rebounded strongly

CSL has seen an increase in their plasma collections of 31% (year-to-date ending October 2023), Grifols reports a 10% increase (year-to-date ending November 2023), Takeda announced a 31% increase (first half of 2022 through first half of 2023), and Kedrion announced a 22% increase in their plasma collections (July 2022 through December 2023). This is a strong rebound from pandemic lows, and so very good news for patients who rely on therapies made from plasma.

U.S. ECONOMIC SITUATION:

Contributed by William English, Ph.D.

The U.S. economy continues to traverse unusual territory, which may create both opportunities and challenges for plasma collections.

Although the rate of inflation — which grew dramatically over much of 2022 and 2023 — has started to fall, the prices of many consumer staples remain high. Recent data suggests that people are currently spending more of their income on food than they have in three decades (about 11% of disposable income). While unemployment remains relatively low, many people are struggling to make ends meet. Moreover, consumer sentiment remains depressed far below what many traditional economic indicators would predict. A recent paper co-authored by former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers argues that this is in part because borrowing costs and difficulty accessing credit remain high. Taking the cost of money into account, their analysis suggests that inflation peaked at around 18%, which is more than double official government estimates. Ultimately, their paper highlights how credit dependent and constrained the American consumer is, particularly at lower income levels.

In this environment, the value of extra cash that can be earned donating plasma should be expected to be highly salient. As long as interest rates remain high, that should provide strong tailwinds for plasma donations even though other indicators may paint a rosier economic picture.

While high food costs and credit costs may encourage more plasma donations, the cost of gasoline remains a wildcard that may have paradoxical effects on donor behavior. There is some evidence that periods of increased gas costs have depressed donations in the past, all else being equal. This effect may be driven by psychological factors that aren’t entirely rooted in a clear economic calculus. However, for donors who have to drive significant distances to reach a donation center, the prospect of knowing one will have to refill a costly gas tank sooner rather than later may keep some at home — at least according to some historic data we have seen.

As of the middle of March 2024, the national average gas price had risen 26 cents per gallon from a month earlier, which also puts current gas prices above what they were this time last year. With ongoing uncertainty in the Ukraine war theater and potential shipping disruptions due to Houthi activity in the Strait of Hormuz, additional gas price volatility and hikes cannot be ruled out. Were gas prices to rise significantly, this could dampen plasma donor turnout among those who have to commute modest distances to reach a donation center.

Ultimately, while some aspects of the economy remain weak and volatile, there should generally be high demand for ways to earn extra cash donating plasma for the foreseeable future. However, despite some tail end risk from global conflicts, the likelihood of dramatic economic volatility appears to be receding, which should be conducive to relatively stable business environments for at least the next few quarters.

ANNUAL REPORTS (CANZUK):

With the UK releasing its immunoglobulin report this past week, all four of the countries whose immunoglobulin self-sufficiency we track most closely have now released their annual data.

Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom continue to be significantly dependent on plasma collected in the United States. 2024 marks a decade since any of these countries were self-sufficient (New Zealand). The UK just restarted their plasma collection program in 2021, but are expecting their first batch of therapies made from UK plasma in late 2024, or early 2025. Australia’s self-sufficiency dropped below 50% once again. There is plenty of news about Canada since Grifols announced three locations in Ontario as part of the partnership between Canadian Blood Services and Grifols.

Immunoglobulin use has returned to pre-pandemic levels. When offering forecasts, each country expects increases in use similar to what the Big Three are forecasting.

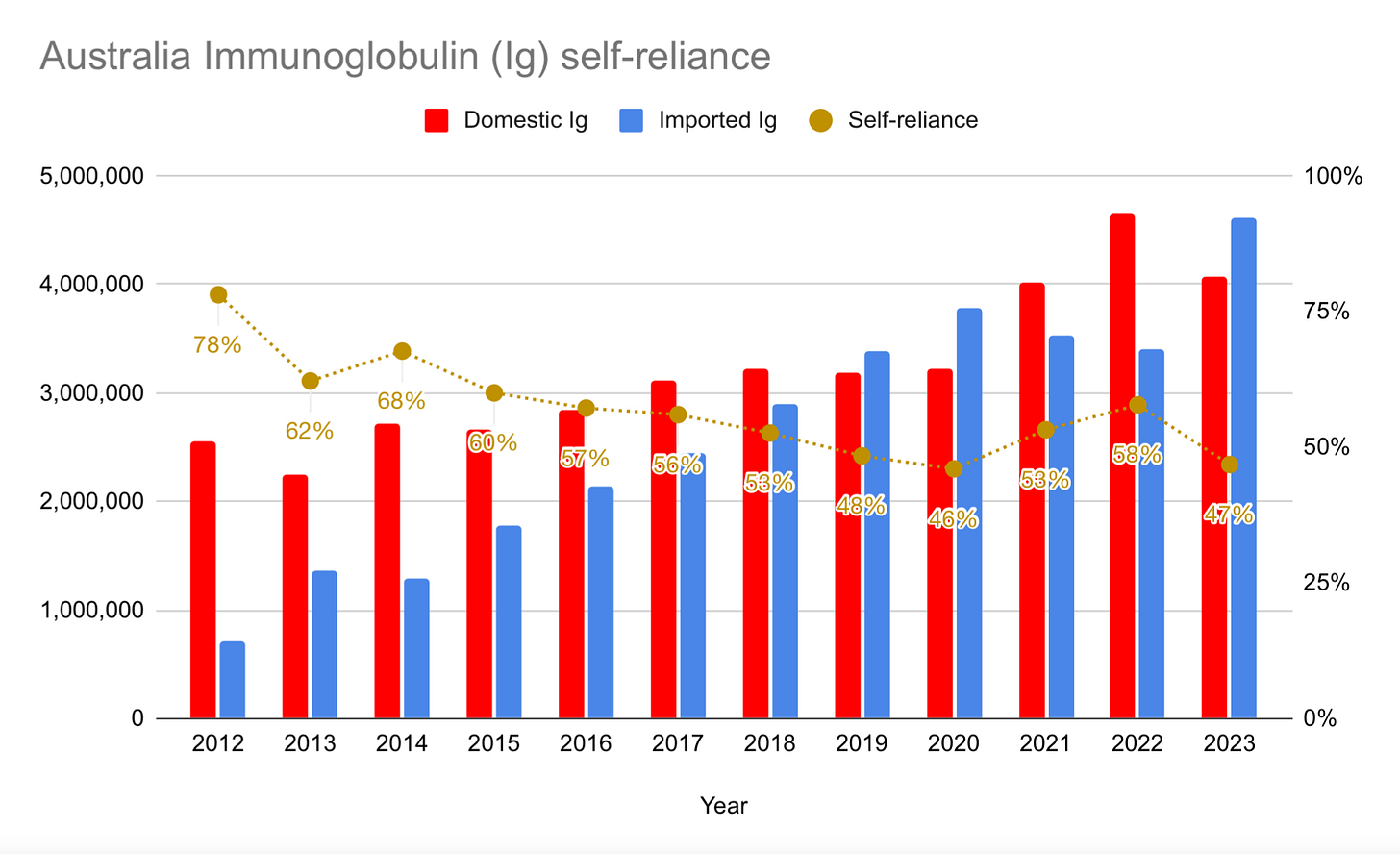

AUSTRALIA

Australia’s self-sufficiency dropped from 58% down to 47%:

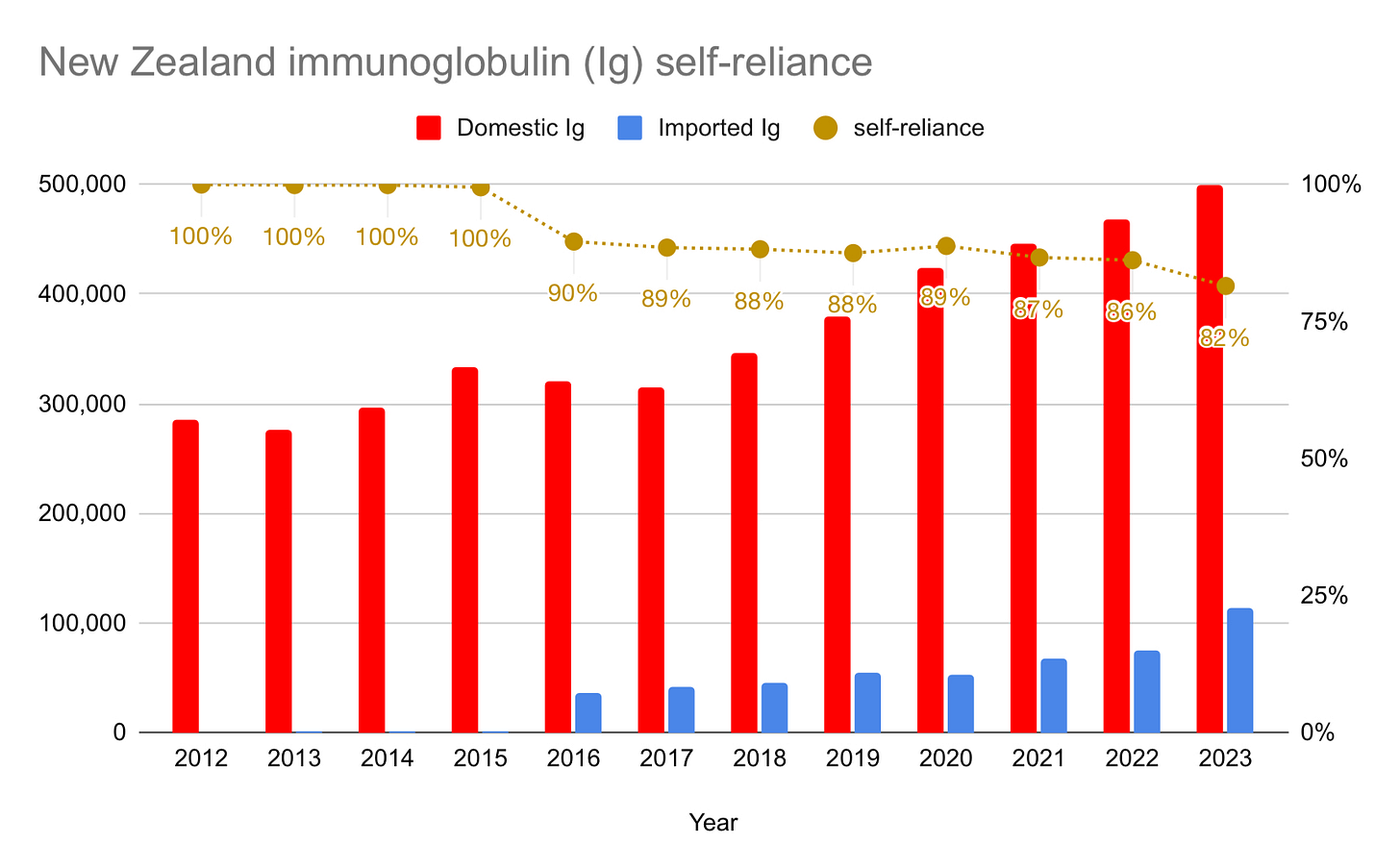

NEW ZEALAND

New Zealand’s self-sufficiency is beginning to drop more significantly. In June of last year, New Zealand Blood Services said they needed 40,000 new plasma donors to meet demand for immunoglobulin. Announced in November of last year, last month saw the end of restrictions on donors from countries affected by variant Creutzfeld-Jakob Disease. New Zealand has a large population of British ex-pats, and so this should help with plasma collection. Despite the additional donors, however, they will not be 40,000 strong, and my guess is that self-sufficiency will decline even further in 2024.

UNITED KINGDOM

The UK continues to be fully reliant on plasma sourced basically entirely in the U.S. This will change beginning in 2024, with the first batch of immunoglobulin manufactured using British plasma expected to be used this year. The UK had a ban on domestic collections of plasma for the manufacture of therapies since 1998 due to variant Creutzfeld-Jakob Disease, a ban that was lifted in February of 2021.

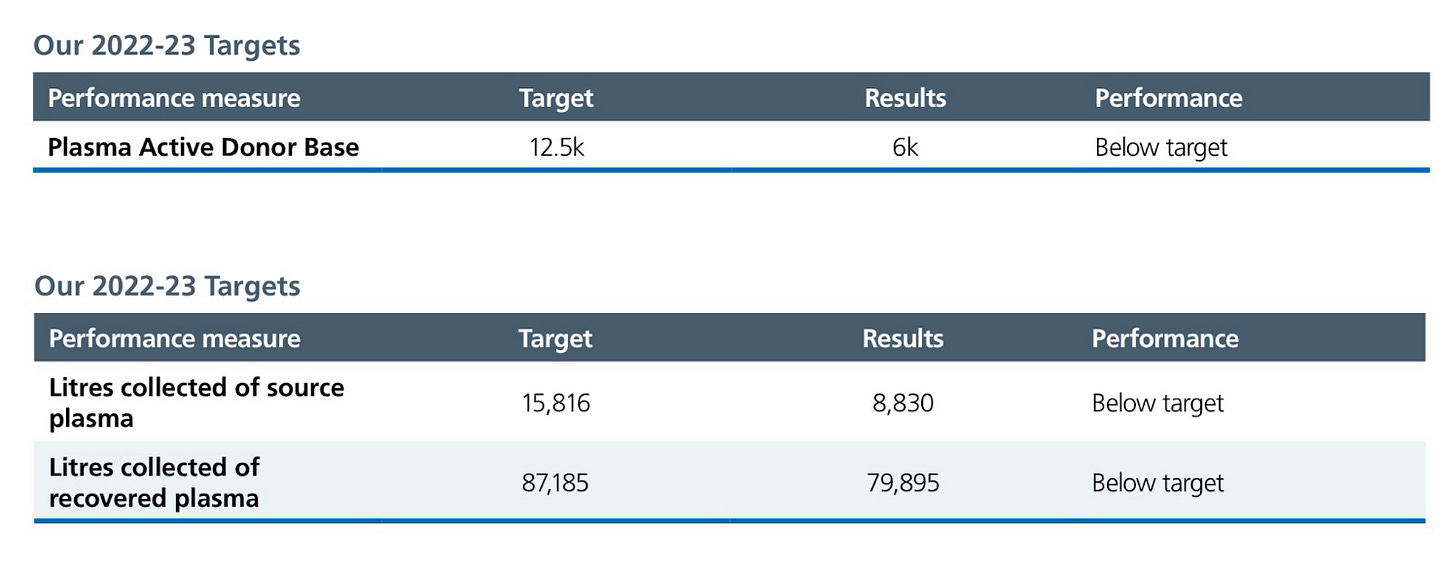

Plasma collection, however, has been disappointing. According to the NHS Blood and Transplant annual report, the UK collected only 8,830 liters of plasma in 2023, significantly missing their target collections of 15,816 liters. They are below target on all of their goals for plasma collection:

CANADA

Finally, here is Canada:

Canada’s plasma supply is once again making news, this time because Grifols announced three locations for their centers in Ontario (Cambridge, Hamilton, and Whitby).

I was cited in this CBC story, a tweet of mine appeared in this Streets of Toronto article, but there were many other stories.

Most of these articles focus on objections raised by public sector unions and an organization called “Bloodwatch” that is funded by public sector unions. Public sector unions oppose the partnership with Grifols, and are the only major opponents of commercial compensated plasma collections in Canada. As a provincially-funded entity, Canadian Blood Services is required to have employees represented by public sector unions, like the Ontario Public Service Employees Union. Companies like Grifols will not have employees represented by these unions, and so permitting commercial plasma collections is seen as a threat to their monopoly on blood and plasma collections.

The most striking feature of these news stories, however, is that they don’t engage patients, nor discuss the position of patient organizations.

Patient organizations have been supportive of compensated plasma collections, and are encouraged by the partnership with Grifols. The Network of Rare Blood Disorder Organizations, representing organizations like ImmUnity Canada, the Canadian Hemophilia Society, GBS/CIDP Foundation of Canada, and ten others, has issued many letters and public statements supporting paid plasma collections as well as the partnership. These are easily accessible on their Advocacy page, any of which could be cited by news organizations if you can’t get a representative on the phone.

This is striking because the current batch of news stories makes it seem as though the most important issue is the jobs of public sector employees. But of course the most important issue is the health and lives of patients and the security of their access to therapies.

Here are the background details:

Canadian Blood Services and Grifols formed a 15-year partnership to increase domestic plasma collections in Canada. The specific details of the partnership (including prices) are not yet public, but we do know the following.

Both CBS and Grifols remain independent entities, with Grifols acting as an “agent” on behalf of Canadian Blood Services. Canadian Blood Services will eventually have 11 plasma collection centers and Grifols will have 15 such centers. Together, along with recovered plasma, the goal is to reach 50% immunoglobulin self-sufficiency “as quickly as possible.” This would require domestic collections of at least 900,000 liters (probably closer to a million), since Canada needed approximately 1.8 million liters of plasma in 2019.

Grifols already purchased a plasma collection center in Winnipeg (formerly Prometic Plasma Resources), as well as a fractionation facility where they will fractionate some volume of domestically-collected plasma (the Montreal-based Green Cross facility). Grifols is currently in the process of acquiring additional plasma collection centers from Canadian Plasma Resources. Canadian Plasma Resources has plasma centers in Saskatoon (since 2016), Moncton (2017), Calgary and Edmonton (2022), and has new centers either open or opening soon in Halifax, Winnipeg, Saint John’s, Regina, and Red Deer. The acquisitions and the three planned centers in Ontario will bring Grifols’ total to 12 centers. Three more centers will be announced soon, although no locations for these centers has been made public yet.

AN AGENT OF CBS

CBS and Grifols believe that this “agency” relationship allows Grifols to collect plasma and pay donors in the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia, where both compensation for plasma donations and private collection of plasma was made illegal in 2014 and 2018, respectively, through a law called The Voluntary Blood Donations Act.

The Premier of British Columbia, however, said on April 16, 2023 that he won’t permit Grifols to operate in that province. I’m not a lawyer, but in my judgement this doesn’t matter. The law explicitly exempts not just Canadian Blood Services, but also “agents” and “successors” of Canadian Blood Services. So British Columbia would need to change the law to forbid Grifols from opening centers there.

Ontario is more interesting.

The Ontario version of the Voluntary Blood Donations Act does not have an “agents” and “successors” clause. Instead, it exempts only Canadian Blood Services. Here’s the relevant text:

CBS has said that the “agency” relationship is implicit in the law, but that’s not obvious. Legal challenges may eventually come before the court. Should such a challenge appear, the courts might rule in CBS’ favor, allowing the centers to move forward, or the Ontario government might amend or repeal the Voluntary Blood Donations Act (the province of Alberta had a similar law, but repealed it in December of 2020).

UNDERSTANDING COLLECTIONS

Many in Canada continue not to understand how much plasma is necessary to meet Canada’s immunoglobulin demand, nor how much plasma is collected via the different routes of recovered plasma, compensated and non-compensated collections.

That confusion is not helped by opponents of commercial compensated collections. For example, back in September of 2022, Kat Lanteigne of Bloodwatch said this: “If CBS can increase the supply to 25 per cent by opening 11 centres, that means they only have to open 11 more and we will be 50 per cent self-sufficient.”

That is not at all what that means.

The 25% figure is not just from CBS’ plasma-only collection centers, but includes recovered plasma obtained from CBS’ whole blood collections, which yield around 200-250,000 liters. Non-compensated plasma collection centers in Canada are likely to average around 15,000 liters per year. To show this, consider collections in Quebec. In 2021, Hema-Quebec published five years’ worth of data on their four Plasmavie plasma-only collection centers. They opened their fourth such center in 2016, and so all four are now operating at or near maturity. In 2021, the Plasmavie centers saw a total of 77,566 individual donations. We do not have data on average collection size, although Hema-Quebec did say that it takes 13,500 donations to yield 10,000 liters, which implies 740 mL per donation. If we generously round that up to 750 mL per donation, we get collections of 58,175 liters in 2021, or 14,544 liters per center.

Here is a very crude screenshot from my files of the five-year performance of the Plasmavie centers in Quebec:

Donor compensation significantly increases collections. An average commercial compensated center operating in Canada is likely to collect at least 40,000 liters per year (although sometimes more, as in Calgary and Edmonton, and sometimes a little less, as is probably true in Moncton). One compensated center performs as well as three or four non-compensated centers.

In summary, to reach 50% self-sufficiency, CBS would need to open at least 30 more plasma collection centers, not 11 as Lanteigne thinks.

This has significant implications on costs.

With similar overhead — including employee, rent, equipment, electricity, and other costs — the more liters you collect per year, the lower is the cost per liter. On average, I estimate the cost of a liter of plasma collected by Canadian Blood Services to come in around $450, while it will cost Grifols around $200. (This estimate is in-keeping with the estimate provided by an Expert Panel looking at Canadian Immunoglobulin Use in 2018, which suggested that paid plasma centers are two-to-four times less expensive than unpaid plasma centers).

Lanteigne continued by saying “there’s no reason why Canadian Blood Services can’t open five centers of their own.”

But now you can see why there are at least two reasons: The volume, and the cost.

OTHER ITEMS OF NEWS:

Europe: Axel Ockenfels and Nobel Prize winner Alvin Roth write about the European SoHO regulations in VOX EU. They defend paying plasma donors. Titled “Consequences of unpaid blood plasma donations,” the article argues that “such legislation jeopardises the interests of both donors and recipients… such rules overlook the effects on donors, on the supply of such substances, and on the health of those who need them.”

Croatia: A discussion of the need to increase plasma collection in Croatia (and Europe) led to some news (Google Translate link). Some insist that plasma collection must be public, though the majority of plasma collected around the world is collected at private plasma centers (mostly in the U.S.). Croatia hopes to collect more plasma but is struggling to keep up with demand:

He points out that they have prepared a plan to increase the amount of collected plasma from the current 22 to 50 thousand liters by 2026.

“What I see is the final amount that reaches my patients and it is not satisfactory and it is not safe. It happened to us that our patients were left without therapy because it was not available,” says Anić.

We are currently experiencing a shortage of medicines based on blood plasma, warns Ivica Belina from the Coalition of Healthcare Associations.

Brazil: Senator Daniella Ribeiro proposed an amendment to the law in Brazil that prevents the private sector from participating in plasma collection and domestic manufacture of therapies. The amendment is being interpreted as permitting the private sector to “collect, process, and sell blood plasma,” which would allow Brazil to have commercial compensated plasma collections. The Bill was approved by the Senate’s Constitution and Justice Committee (by a 15-11 vote) in October, and now needs to get the support of 3/5ths of senators in two rounds of voting.

U.S.: A student at the University of Notre Dame (Jessica Robertson) whose mother is a nurse writes a positive story about blood plasma donations in their student newspaper entitled “Plasma donations must take center stage.”

PRESENTATIONS

William English and I had a chance to present our findings about the impact of compensated plasma collections on non-compensated blood collections in Canada and the U.S. at the 5th European Conference on Donor Health and Management in Vienna.

Our findings suggest that these opportunities attract different individuals, since we found no negative effect. The paper has received a Revise & Resubmit at an economics journal, and we hope to see it published soon.

I had a chance to speak about plasma before audiences at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, at Dalhousie University in Halifax, and at Toronto Metropolitan University in Toronto.

PEER-REVIEWED:

The Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association has been tracking impact of donation frequency on donor health for a while. Most recently, they released some of their findings in Transfusion. Entitled “Effects of donor frequency on U.S. source plasma donor health,” the article, written by Michelle Fransen, Mark Becker, Janet Hershman, James Lenart, Toby Simon, Kristen McCausland, Alexandra Parfitt, and Lisa Weissfeld, focused on self-reported measures of health and well-being. The study had 5,608 participants from 14 U.S.-based plasma collection centers. The result is no statistically significant differences in self-reported health outcomes (using the SF-36v2 Health Survey) regardless of frequency of donations as compared with new donors. They conclude:

“The self-reported data in this study support the hypothesis that compensated donations at US FDA permitted frequencies and volumes are consistent with maintaining donor health. Compared with the general population, SP donors have comparable or better health than the general population.”

Along with Mark Wells, a philosophy professor at Northeastern University, I have a chapter in an Oxford University Press edited volume entitled Exploitation: Perspectives from Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, edited by Matt Zwolinski and Ben Ferguson.

The chapter is entitled “Exploitation does not justify prohibiting Canadian paid plasma,” but the argument applies to, for example, each of the European Union countries as well and so could also have been titled “Exploitation doesn’t justify prohibition anywhere in the European Union either.”

You can read an early version of the chapter here.

I also published a chapter on altruism and commodification for the Routledge Handbook of Commodification, edited by Vida Pantich and Elodie Bertrand.

The chapter is entitled “Blood and Plasma: Or, if you’re such an altruist, why don’t you sell your plasma?” In it, I argue that neither the altruism nor the commodification objections to compensated plasma collections stand up to scrutiny. Genuine altruists shouldn’t care if they are paid to donate or not, since it helps patients either way.

You can read an early version of that chapter here.

NEXT TIME:

In the next Quarterly, we’ll look at the effect of the pandemic on average plasma collections in the United States and give you a rundown on where plasma centers are in the U.S., and how many there are. We will also take a look at the existing Latent Therapeutic Demand studies for certain indications for Immunoglobulin, on top of the usual reports from the Big Three, news updates, and academic research.

If you got this far, and find this useful, please share it with your friends and neighbors, and anyone else who is as interested in the world of plasma as you seem to be. Thanks for reading!