It’s June of 2024, and we still do not collect enough plasma.

While many countries collect enough blood and plasma for transfusion, almost none collect enough plasma to meet the needs of their domestic patients, especially immunoglobulin.

And since the point of plasma collection is to collect enough to meet the needs of the patient communities the collector serves, failing to collect enough is failing at the most important job a system of plasma collection has. It doesn’t matter if the system provides an opportunity for donors to express their altruism, or a reason for people to feel a sense of civic pride, or stitches people together through community or national solidarity. If your country’s system of plasma collection doesn’t collect enough plasma, then it can only be described as doing a poor job of it.

Probably, it needs to change.

Only a handful of countries manage to collect enough plasma to meet the therapeutic needs of their patients. These countries have policies that result in reliable, safe, and efficient systems of plasma collection. The surplus plasma collected by these systems helps to “top up” or subsidize the poor performance of other high-income countries’ collection systems.

They also help some low- and middle-income countries access some of their surplus plasma-derived medicines. But since the need is so great and is growing each year, too many patients in low and middle-income countries simply go without. That’s if their need is discovered at all.

In the European Union, only four of the 27 Member States collect enough plasma: Germany, Austria, Hungary, and the Czech Republic. They each have plasma collection surpluses. These countries have good systems of plasma collection.

The other 23 Member States have plasma collection shortfalls. These countries have poorly-performing systems of plasma collection.

What distinguishes the four that collect enough from the 23 that don’t is probably not greater altruism or superior solidarity. You can take a look at the Global Preferences Survey, which tries to measure altruism amongst other things, or the Solidarity Index from Global Solution, and try to find some correlations, but I don’t think you’ll find anything meaningful. While it’s true that Germany and Austria score near the top on both measures, Hungary and the Czech Republic score near the bottom.

Instead, what distinguishes the four from the 23 is that the four that collect enough allow the participation of the commercial sector in plasma collection, and permit the use of donor compensation in the form of a fixed-rate allowance. The 23 that fail to collect enough forbid these practices, although they do make use of a wide variety of incentives apart from direct compensation.

ALL ABOUT DENMARK

Denmark does not allow commercial participation in plasma collection, and they don’t allow donor compensation either. But many are confident that Denmark will reach self-sufficiency very soon, without changing their laws about who can collect plasma, and without use of donor compensation.

If they do succeed, they will break a decade’s-long trend. This year marks the ten-year anniversary since the last time a country managed to be self-sufficient in plasma for medicines without help from the commercial sector, and without using donor compensation. That was New Zealand back in 2014.

Since 2014, however, New Zealand Blood Services has reported growing plasma collection shortfalls. You can see the details in the last quarterly, but the last few years saw New Zealand’s shortfall grow from 13% in 2021 to 14% in 2022 to 18% in 2023.

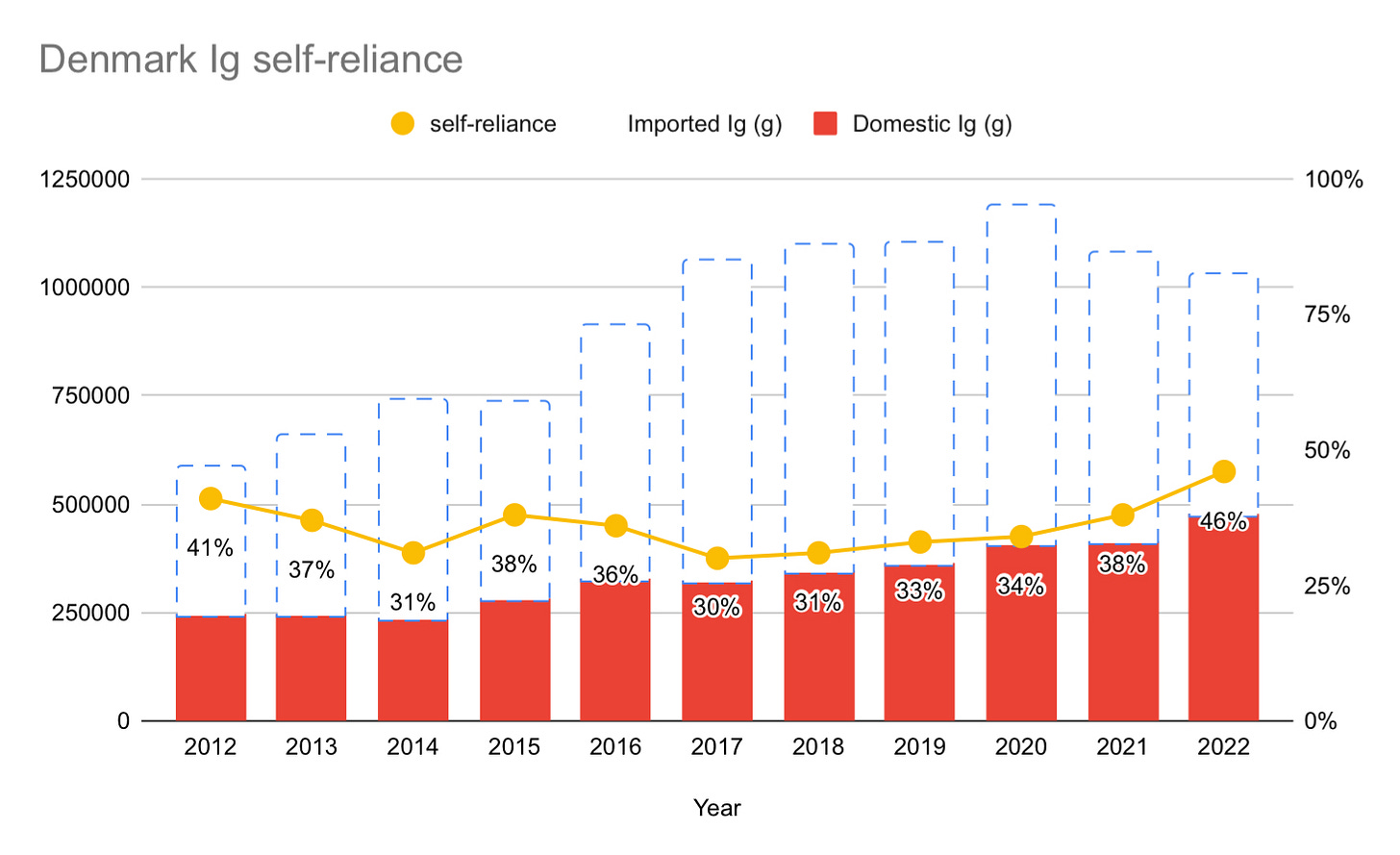

But unlike New Zealand, Denmark has seen their gap between supply and demand shrink over the past seven years. Since 2017, Denmark has consistently shrunk the gap. In the most recent data from 2022, Denmark decreased the gap by 8% from 2021, by increasing their plasma collection by an impressive 24%.

Improvements like this are why some are so optimistic about Denmark.

The optimists include Dr. Fritz Schiltz from the Belgian Red Cross. I met Dr. Schiltz at KU Leuven in Belgium where I presented data on plasma collection in selected countries, and spoke about the ethics of allowing commercial assistance and donor compensation for plasma collection. The conference was sponsored by the Belgium Red Cross, and held on June 7th.

During the Q&A, Dr. Schiltz told me that Denmark will be self-sufficient in the next few years, and also that Belgium will be self-sufficient within five years. We made a friendly bet on Belgium. I don’t think Belgium will be self-sufficient unless they enlist the help of the commercial sector or introduce donor compensation, while Dr. Schiltz thinks they will do it using the current model.

Will Denmark do it in a few years? I think it’s unlikely, but here is the data:

As you can see, Denmark still has a long way to go to reach self-sufficiency. You can get a bit more insight about Denmark from a recent (2022) presentation by Morten Bagge Hanson here.

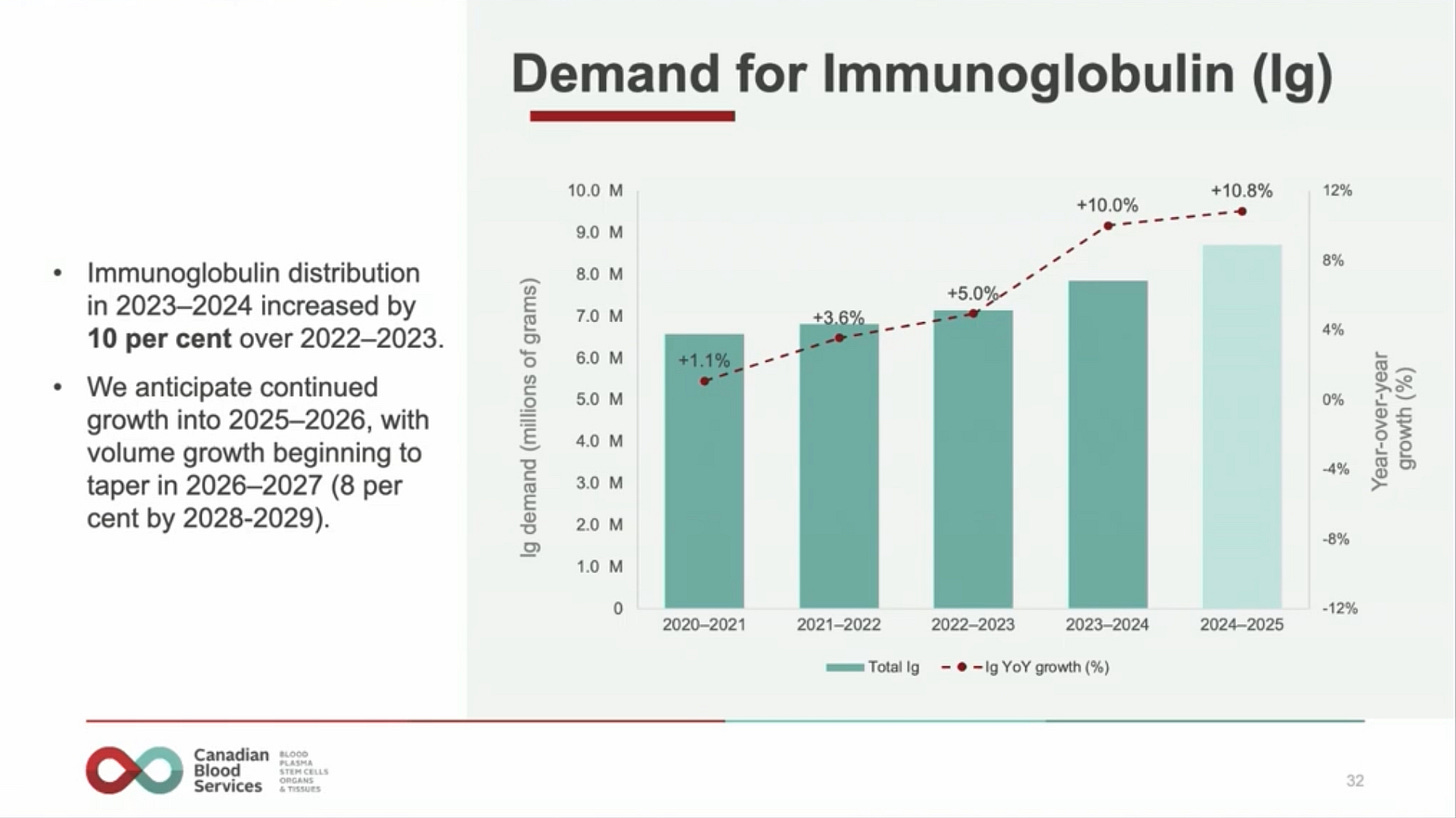

While the self-sufficiency numbers look promising, they are not as promising as they might at first appear. The reason why is because Denmark has not yet rebounded from the decreases in immunoglobulin use as a result of the pandemic. That use is likely to see a significant (around 10%) increase in 2023 or 2024. This is what happened in comparable countries like New Zealand and Canada. New Zealand saw immunoglobulin demand grow by 12.9% from 2022 to 2023. Canada saw 10% growth from 2023 to 2024. At the most recent Canadian Blood Services’ annual meeting, they projected at least another year of double-digit growth for 2025:

Denmark opened two plasma-only collection centers in 2020, one in Aarhus in September, the other in Odense in November. In 2022, these centers contributed 6,600 and 6,400 liters respectively. While this helped Denmark improve sufficiency, these collection volumes are very small. In Germany, for example, a large plasmapheresis center will collect 50,000 liters in a year, while the average collection volume for commercial plasma collectors in the EU was well over 20,000 liters per center in 2022. It would be interesting to see what the cost is per liter of plasma collected in Danish plasmapheresis centers, though I don’t have those figures.

Denmark has now opened a third center, and there are plans to open two additional centers which will cover each of Denmark’s five regions.

IG CAN’T INCREASE FOREVER

Denmark’s immunoglobulin use ranks amongst the highest in the European Union, at 174 g/1,000 in 2022. That’s down from a high of 203 g/1,000 in 2020, but still well above the European Union average which stood at 81 g/1,000 in 2020.

For comparison, Belgium was at 218, Sweden at 177, France also at 174, and Italy at 111 g/1,000 in 2020. Outside of the EU, New Zealand and the UK used 96 and 86 g/1,000 respectively that same year, but Canada, Australia, and the United States used 241, 273, and 334 g/1,000.

The optimistic case for Denmark (and Belgium) appears to depend on four things: The hope that demand for immunoglobulin can’t increase forever; the suspicion that maybe there is too much immunoglobulin use as it is; the expectation that plasma collections will increase; and, finally, the belief that immunoglobulin yield per liter will increase to 5 grams per liter sooner rather than later. Let’s look at each of these.

There is little doubt that Denmark (and Belgium) will increase plasma collections by opening additional plasmapheresis centers. Similarly, yields should improve as well, though this may still take more time. At present, Denmark uses an estimate of 4 grams per liter for their self-sufficiency calculations (just for comparison, the data from Italy implied a yield of 4.31 grams per liter in 2021). Increased collections and improving yields provide some reasons for optimism.

Unfortunately, there is little hope that demand will slow. “Forever” is an exaggeration, but we can be fairly confident that this decade is most likely to continue to see the kind of annual increases in demand we’ve witnessed in the two decades prior. From 2000 through 2020 we witnessed 8.7% annual growth in global demand, with Europe growing 6.7% annually between 2014 and 2020. To get a really good sense of these trends, take a look at the Marketing Research Bureau’s Data & analysis of immunoglobulin supply and plasma requirements in Europe for 2010 - 2021.

The case against optimism is based on the following: First, the industry is telling us that they expect demand to continue to grow. CSL, Grifols, and Takeda have offered projections of 6-8%, “high single-digit,” and 5-8% growth, respectively. They are growing their U.S.-based collection fleets in line with these projections. I will give more details about this in the next Quarterly, but as of June 29, there are 1,224 active plasma collection centers in the U.S. FDA database, up by 19 since February of this year, and up 32% compared with the 832 centers in operation just five years ago in 2019.

The industry is also investing in additional fractionation capacity. CSL opened their 9 million liter fractionation center in Broadmeadows in Australia in December of 2022, representing an AUD$900 million dollar bet on continued increases in demand. Takeda just broke ground on a US$230 million dollar expansion of their Los Angeles facility earlier this month. Others are also expanding or planning to expand capacity.

The second is that, despite some claiming that we are “overusing” immunoglobulin, there is very little support for this claim. Instead, the peer-reviewed literature on latent therapeutic demand for immunoglobulin suggests the opposite — apart from the U.S., Canada, and Australia, other countries, including Denmark, are most likely still underusing immunoglobulin. Let’s look at this in more detail.

LATENT THERAPEUTIC DEMAND

Latent Therapeutic Demand is the demand for a therapy if every person who needed it were discovered in a population and made use of the therapy. Here are the LTDs for immunoglobulin for specific indications (all of these are the kinds of ailments where immunoglobulin is unquestionably the appropriate treatment):

An estimate published in 2014 put the LTD for Common Variable Immune Deficiency (CVID) and X-linked Agammaglobulinemia (XLA) at 72 grams / 1,000.

Published in 2018, an LTD estimate for Primary Immune Deficiencies (PID) put the figure at 105.1 grams / 1,000 (+/- 88.5 grams). This included CVID, XLA, Severe Combined Immune Deficiency (SCID), hyper IgM syndrome, and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome.

Published in 2019, a separate estimate for PID also put the LTD figure at 105 grams / 1,000, and added neurological conditions at 138 grams / 1,000. Together, these indications give us an LTD of 250 grams / 1,000, an amount the authors noted “reflects the current Ig usage in the USA and other countries such as Canada and Australia.”

Finally, a 2021 LTD estimate for CIDP, Guillain-Barre Syndrome, and Multifocal Motor Neuropathy put the figure at 83.05 (+/- 24.5), 6.1 (+/- 3.2), and 36.1 (+/- 25.5) grams / 1,000 respectively, for a total of 125.25 (+/- 53.2) grams / 1,000. Here, the authors note that “current Ig usage reflects the estimated LTD for the main indications for Ig in the United States.”

In short, LTD estimates provide support for the view that Ig use rates in Canada, Australia, and the United States are not inappropriately high. If anything, they more closely track LTD figures than others.

For more on this, take 20 minutes to watch Dr. Albert Farrugia’s video presentation entitled “The estimation of immunoglobulin demand against a background of uncertainty” which he kindly posted on YouTube:

In the video, Dr. Farrugia highlights the case of Australia. Australia’s use is second-highest in the world at 323 grams / 1,000 in 2023. So if any country is “overusing” it, Australia would be. But Dr. Farrugia insists that Australia’s system is very strict. Prescribing immunoglobulin in Australia is not a simple matter, with several layers of checks to ensure that this therapy is appropriate.

Overall, the investments by industry and the evidence from LTD data provide us with as good a case as can be made that demand growth in this decade will resemble the annual growth in the prior two decades. And this gives us little reason to be optimistic about Denmark (and Belgium) becoming self-sufficient without support from the commercial sector, or the introduction of donor compensation. But we’ll see.

THE BIG THREE FIVE

To give a better sense of the direction of the industry as a whole, I’ve decided to expand coverage of reports from what I’ve been calling “The Big Three” of CSL, Grifols, and Takeda, to now “The Big Five” including Octapharma and Kedrion.

The quick recap is that revenue for immunoglobulin continues to rise, demand for immunoglobulin remains strong, cost-per-liter at U.S. collection centers continues to decline, while plasma collections continue to rebound strongly from pandemic lows.

Revenue from and demand for immunoglobulin continues to grow

In their half-year results, CSL Behring reported a 23% increase in revenue for Immunoglobulin, and said that “Underlying patient demand for Ig in core indications remain strong.” IVIg represents 35% of CSL Behring’s revenue, with SCIg now making up 18%, for a total of 54% of revenues.

Grifols announced that their “immunoglobulin franchise grew by 13% cc,” growth that “builds on the expected double-digit growth of the immunodeficiency market.” Takeda saw their immunoglobulin product revenue grow by 17% in their FY2023. Octapharma said that sales were up 14.4% (this would include immunoglobulin). Kedrion has not yet released an updated report.

Plasma collections are strong

CSL did not give specific numbers, but did say that “Plasma collections remain strong.” Grifols said that their plasma supply “increased by 8% in the first quarter” and that “the outlook for plasma remains positive going forward.” Takeda reported 21% growth in their plasma volume, and is planning a more-than 50% increase in their manufacturing capacity from FY2023 to FY2028. Octapharma reported record revenue with “a substantial increase in plasma collection,” while Kedrion is yet to release more recent figures.

Cost per liter continues to trend downward in U.S.

CSL reported a further 10% decrease in cost per liter (on top of a 14% decrease announced in their 2023 annual report). Grifols said their cost-per-liter “declined by 2% in March compared to December 2023.” I did not see any comments on cost-per-liter by Takeda, Octopharma, nor Kedrion, but assume they are trending downwards for each of these as well.

CSL Behring announced that they will continue their roll-out of the RIKA plasmapheresis device over the next 18 months, which they say has reduced donation times by around 30%.

NEWS:

Greece to allow commercial plasma collection: The biggest news over the past three months was the April 16 announcement by Adonis Georgiadis, Health Minister of Greece, that they will change the law to permit commercial participation in plasma collection. The Minister said, “I want to send you a clear message: our government, a business-friendly government, a reformist government, is absolutely willing to change the legislation in a direction that will allow the field of plasma collection to develop as quickly as possible.”

The news was announced at the PPTA’s International Plasma Protein Congress hosted in Athens, Greece.

Hopefully this sets a precedent for other European countries to consider changing their rules as well.

Egypt announces self-sufficiency: On February 21st, Grifols announced that their partnership with the Egyptian government has succeeded in making Egypt self-sufficient in immunoglobulin for the first time. They also said that they expect plasma collections to double in 2024, and that they will open their 10th of 20 planned centers soon. The partnership was initially formed in 2020.

I don’t have access to the data on immunoglobulin use nor on plasma collections, so while this is good news, it is hard to know exactly how good. Please do reach out to me if you know where I might access this data.

Grifols announces three locations in Ontario: Grifols says that their first Ontario-based locations will be Whitby, Hamilton, and Cambridge.

With the acquisition of centers from Canadian Plasma Resources and Prometic Plasma Resources, Grifols has 11 locations in Canada — in Saskatoon, Regina, Moncton, Fredericton, Saint John, Winnipeg, four locations in Alberta, and a soon-to-be-opened center in Halifax, Nova Scotia. I’ve visited their center in Saskatoon when it was Canadian Plasma Resources, and peeked in the window of their not-yet-opened center in Halifax. Halifax is also now home to Drumlin Plasma, which I visited when I spoke about plasma at Dalhousie University on March 14th.

Hamilton a “paid plasma free zone”: Earlier this month, Hamilton, one of the three proposed sites for a Grifols center, declared themselves a “paid plasma free zone.” The declaration is symbolic, has no legal force or effect, and is unlikely to have any impact apart from a few news stories.

The mayor of Hamilton, Andrea Horwath, was leader of the Official Opposition New Democratic Party in Ontario in 2014 and played an important role in helping to pass the Voluntary Blood Donations Act, the law that bans commercial compensated plasma collections. But, as discussed in the last Quarterly, the Act includes an exception for Canadian Blood Services. Grifols and Canadian Blood Services believe that Grifols can operate centers in Ontario (and British Columbia) as an “agent” of Canadian Blood Services.

PEER REVIEWED

The most interesting peer-reviewed article to come out recently, that is bound to be discussed often, is a paper by John M. Dooley and Emily A. Gallagher entitled “Blood Money: Selling plasma to avoid high-interest loans,” in The Review of Financial Studies.

The paper shows that in jurisdictions that see the introduction of opportunities for compensated plasma donation, “demand for payday loans falls by over 13% among young borrowers.” That means that in jurisdictions without this opportunity, young people turn to high-interest payday loans more often.

Another great paper is by Julio J. Elias, Nicola Lacetera, Mario Macis, Axel Ockenfels, and Alvin E. Roth. Titled “Quality and safety for substances of human origins: scientific evidence and the new EU regulations,” published in BMJ Global Health, the authors summarize empirical evidence showing that “carefully designed (donor) compensation can increase the supply of SoHOs without negatively affecting quality and safety,” and also respond to a number of moral objections to the use of compensation.

Elena Koch and a long list of co-authors published the very interesting “Incentives for plasma donation” in Vox Sanguinis. The paper, which I mentioned further above, discusses the wide variety of incentives used by different blood and plasma collectors in 26 countries.

Albert Farrugia, whose work on Latent Therapeutic Demand was discussed above, along with several co-authors published a report of their workshop discussion at the joint International Society for Blood Transfusion (ISBT) and International Plasma and Fractionation Association (IPFA) conference. Published in Vox Sanguinis, the article, entitled “Generating pathways to domestically sourced plasma-derived medicinal products,” looks at ways to increase self-sufficiency in plasma medicines without relying on commercial assistance (nor donor compensation). The paper is interesting, and I suppose I understand why a discussion of public-private partnerships similar to the ones Grifols has formed in Egypt and Canada might be either out of scope or off the table for workshops hosted by the ISBT and IPFA. Although I will say that I would be eager to read articles with a broader set of options for consideration.

Finally, in “Limited evidence, lasting decisions: How voluntary non-remunerated plasma donations can avoid the commercial one-way street” Kelsey J. MacKay, the aforementioned Fritz Schiltz, and Philippe Vandekerckhove argue that introducing commercial compensated collections may be unsafe for donors and that once you allow payment, you can’t go back (it’s a “one-way street”).

Without giving a complete response, I can’t help but note that we have many examples of this “one-way street” being a two-way street. Spain used to permit payment, then banned it. The U.S. went from paying most blood donors, to basically none at all after the FDA passed a labeling law in 1978 requiring paid-for donations to be labeled as such. Eastern European countries used to pay donors, a practice that has all but stopped. The Czech Republic’s national blood operator paid for all apheresis donations, but then stopped paying plasma donors when the Czech Republic saw the introduction of commercial collections in late 2006 (interestingly, these donations increased fairly significantly when they went from paid to unpaid). And so on.

There are numerous other cases like this. It is not a “one-way street” and never has been.

The article also unhelpfully conflates the issue of payment with the separate issue of donation frequency. It suggests that twice-weekly plasma donations can reduce IgG levels to below medically acceptable levels. Even if so, this is not an argument against commercial collections nor donor compensation. Donation frequencies are set independently of who is in charge of collections or whether or not donors receive compensation, as are the rules regarding the frequency of checking IgG levels through total serum protein tests. For example, the Czech Republic allows once-every-two-weeks donations, and Germany requires total serum protein checks every fifth donation, but both allow commercial compensated plasma collections.

Finally, comparisons to the United States seem inapt. Instead, critics of commercial compensated collections in the EU should compare their systems to Germany, Austria, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, not the United States. Moving to a U.S.-style system would require adjustments to the recently passed SoHO legislation, which won’t happen, while moving to a German-style system is compatible with the SoHO legislation and is something actually being considered by EU countries (for example, Greece!).

FEEDBACK

In the last Quarterly, I cited a donor safety study that showed long-term, frequent plasma donations were safe. Peter O’Leary, the Executive Director of the European Blood Alliance, reached out to me to ask me to post the response article written by him, Hans Van Remoortel, Katja van den Hurk, Veerle Compernolle, Pierre Tiberghien, and Christian Erikstrup. The article is entitled “Very-high frequency plasmapheresis and donor health — absence of evidence is not equal to evidence of absence,” and was published as a commentary in Transfusion back in November of 2023.

Please reach out to me if you have feedback, or would like me to include some item you think I may have overlooked. If you believe I have made a mistake in any of my numbers or data, please let me know right away so that I can fix it. Finally, if you happen to know where I might get data on Belgium, Mexico, Egypt, countries within South America, or South-East Asian countries, please also reach out to me.