America’s plasma contribution to the world

All about blood plasma collection in the United States

As of today, the United States is home to 1,234 active plasma collection centers according to the FDA database. If you include Puerto Rico, it’s 1,237.

For comparison, that’s more centers than there are Firehouse Subs (1,213) or Long John Silver’s (1,200) locations. (These are popular food chains in the U.S. and Canada).

There are more plasma collection centers in the U.S. than anywhere else in the world not only in absolute terms, but also per capita. There is one plasma center for every 271,235 people in the U.S.

I’ve been tracking the total number of centers each month since February. At the end of that month, the U.S. had 1,205 active centers, meaning that from then until November 15th, the U.S. added 29 centers.

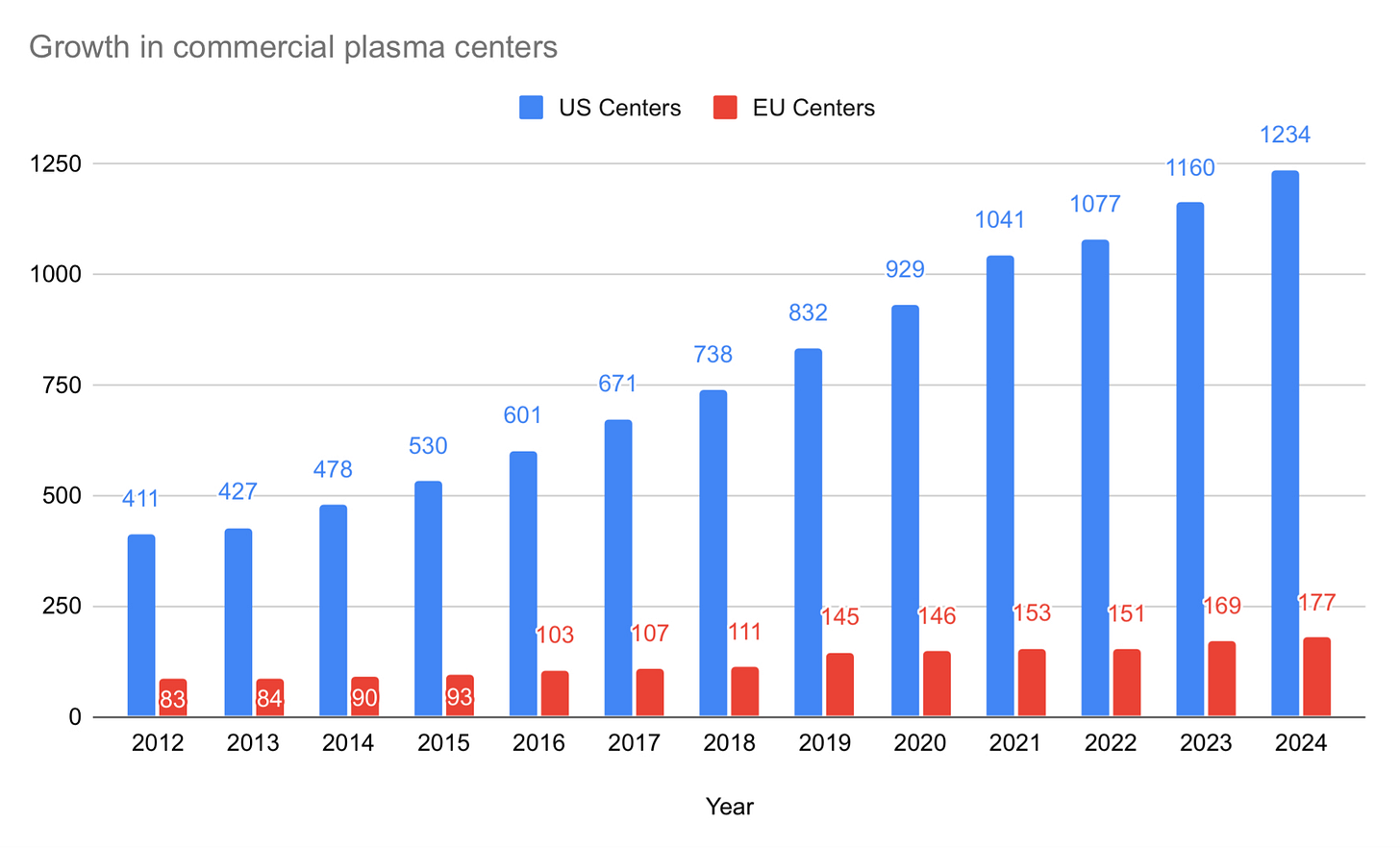

Here is what center growth looks like from 2005 until today:

Over the ten years from 2005 to 2015, the U.S. added 231 centers (from 299 to 530), representing 77% growth at 5.89% per year. The most recent 10-year period from 2014 until today saw the U.S. add 756 centers (from 478 to 1,234), representing 189% growth at 11% per year. It took 11 years to double the number of centers from 2005 to 2016, but then took only seven years to see that number double again from 2016 to 2023.

Such remarkable growth raises two important questions. The first is, Why has plasma collection grown faster in the United States than anywhere else in the world? And the second is, Will this continue?

WHY IS PLASMA COLLECTION GROWING SO FAST IN THE U.S.?

The answer to the first question is two-fold: The rise in plasma centers in the U.S. roughly corresponds to the global increase in demand for immunoglobulin, which grew at a rate of 8.7% from 2000 through 2020.

During that time, governments around the world decided against investing in the kind of plasma collection infrastructure necessary to keep up with demand growth, while also maintaining bans on such investment by the commercial sector. So the commercial sector continues to grow where it can, which is primarily in the U.S., but also in Germany, Austria, Hungary, and the Czech Republic.

Here is center growth in Europe (which includes Ukraine) compared with the U.S. from 2012:

Europe nearly doubled the number of commercial centers in the 10-year period from 2014 until today. Europe added 87 centers, going from 90 to 177, which represents 97% growth at a 7% annual pace.

While Europe is attractive, the U.S. continues to have a more open regulatory environment that attracts more investment. Donors can give more often, and companies have more flexibility in terms of how much they pay donors (in Europe, compensation is a flat-rate allowance set by governments).

Of course CSL, Grifols, and Kedrion would be very happy to operate in their home countries of Australia, Spain, and Italy, but their home countries forbid it. So each of them operate centers in the U.S. to make therapies that in part help shore up the shortfall in their home countries.

To illustrate this: In 2023, Australia imported 4.6 million grams of immunoglobulin, which requires around 1.154 million liters of plasma (we’ll assume 4 grams of Ig per liter). In the U.S., the average, fully mature center collects about 50,000 liters per year. That means that around 23 centers operate in the U.S. just for Australian patients.

Spain imported over 3.2 million grams of Ig in 2022, which means there are about 16 plasma centers in the U.S. collecting plasma for Spain. Also in 2022, Italy imported over 2.2 million grams of immunoglobulin, which required about 11 centers in the U.S. collecting plasma for Italy.

In total, about 50 centers operate in the U.S. to shore up plasma collection shortfalls in Australia, Spain, and Italy.

My home country of Canada imported just over 7.5 million grams of Ig in 2023, representing the plasma collection of nearly 38 centers in the U.S. CANZUK as a whole (that’s Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom) imported nearly 19 million grams of immunoglobulin in 2023, which represents the collection volume of about 94 U.S. plasma centers.

WILL THIS GROWTH CONTINUE?

As for the second question, I think the answer is yes. My expectation for this year was that the U.S. would equal or exceed 1,250 centers. With a month left to go, it looks like we’ll miss that number by about a dozen centers. But we will get there.

Here’s my prediction: Over the next three years, I expect 8% annual growth in plasma collection centers in the U.S. If I’m right, then the U.S. will be home to 1,333 centers next year, 1,439 by 2026, and 1,554 by 2027.

But there’s good reason to think that we will continue to see 11% annual growth in plasma collection over the next three years as we’ve seen over the past 10. If so, then there will be 1,688 centers operating in the U.S. by 2027.

I don’t see anything happening around the world at the moment that will significantly impact the global plasma collection landscape over the next five years. We have seen an important shift towards greater openness to commercial plasma collection since 2020, a trend that I expect will continue. The most interesting trend to watch is the emergence of a public/private partnership model (which I’ll discuss in more detail in the next Quarterly). Grifols created the first of these in 2020 with Egypt, and then created a similar partnership with Canadian Blood Services in 2022. Meanwhile, Uzbekistan formed a partnership with a Chinese plasma company, with the first of their centers opening last month.

The additional plasma collected in places like Uzbekistan and Egypt is unlikely to affect demand for U.S. source plasma, since they are regionally focused and are more likely to result in greater use of plasma therapies in those regions. Other countries like Ukraine and, soon, Greece, will help, but the volumes will not be large enough to affect the global dynamics.

Only the partnership with Canada is likely to have any noticeable impact on U.S. plasma collection, and this will be small. As mentioned, Canada’s needs are currently equivalent to 38 centers, which represents about 3% of U.S. collections. Canada is likely to go from its current 16% self-reliance (19% including Quebec), to about 25% by end of this year, and 50% over the next two to three years. However, demand for immunoglobulin in Canada grew by 10% last year, and will likely see another year of 10% growth before returning to 6-8% growth the year thereafter. So the net impact of Canada’s policy shift can be understood as equivalent to dampening center openings in the U.S. by about 15-20 centers over the next five years.

U.S. COLLECTIONS BY REGION

In terms of absolute numbers, Texas is home to the most plasma centers at 178. Remarkably, there are as many commercial plasma centers in the state of Texas as there are in all of Europe which is home to 177 centers according to PPTA data (including Ukraine).

Florida is second with 94 centers, and California has the third-most plasma centers with 63. The top five states for plasma centers look like this:

Just for fun, we can look at plasma collection deficits in other countries and pair them up with various states.

So, for example, Canada’s imports equal about 38 centers’ worth of collections, which is identical to the number of centers in the state of Indiana.

Australia needs about 23 centers’ worth of plasma, which is exactly the number of centers in New York.

The CANZUK region as a whole needs about 93 centers’ worth of collections, which is nearly as many centers as there are in Florida (94).

Belgium imported about 1.3 million grams of Ig in 2022, which is equivalent to 6 centers, or the number of centers in the state of New Mexico.

France imported about 8.3 million grams of Ig in 2022, the equivalent of 42 centers, which is almost as many as in the state of Pennsylvania (43 centers).

CENTERS PER CAPITA

A different picture emerges if we look at the numbers relative to population.

Despite Texas’ large absolute number of centers, Texas drops to sixth in per capita terms with one center for every 171,367 residents. Florida drops from 2nd all the way to 29th per capita with a center for every 240,540 Floridians.

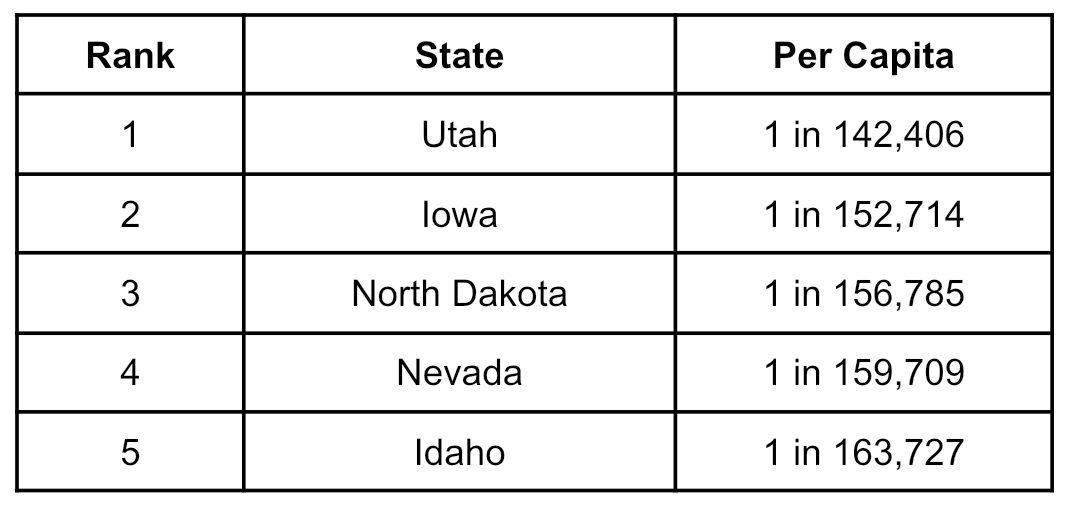

Instead, it’s Utah which is home to the most plasma centers per capita with a center for every 142,406 Utahns. Iowa comes in second with a center for every 152,714 residents, and North Dakota takes third place with a center for every 156,785.

Overall, the United States averages one plasma center for every 271,235 residents, while the top five states look like this:

To give some context to these figures, consider how these numbers compare to the country I discussed in my last Quarterly, Denmark. Denmark has a population of 5.9 million, and is home to four plasma centers. That means there’s one plasma center for every 1,475,750 Danes.

Wisconsin has about the same population as Denmark (5.9 million), but is home to nearly eight times as many centers at 31, or a center for every 196,457 Wisconsites.

Meanwhile, Denmark imported just over 600,000 grams of Ig in 2023, which means that about three centers operate in the U.S. to help make up for Denmark’s plasma collection shortfall. That’s as many centers as operate in the state of Wyoming.

STATES WITHOUT CENTERS

There are still four states and the District of Columbia without any plasma collection centers.

Alaska and Hawai’i have no plasma collection centers, most likely because of geographic challenges (Hawai’i used to have them, but they were probably too expensive to operate). The District of Columbia has no centers, and that’s probably due to the high cost of real estate.

Meanwhile, two surprising states with no centers are Vermont and New Hampshire. My suspicion is that the regulatory environment in those states is poor, just as it has been in nearby states like Massachusetts (home to just seven centers, or one for every million residents), Connecticut (with just one center despite a population of over three and a half million), and New York (with a growing fleet of centers now numbering 23, though that’s just one for every 850,922).

THE BIG FIVE

Revenue from immunoglobulin continues to increase by double digits, plasma collections continue to be strong, and cost per liter continues to decrease.

Revenue from immunoglobulin continues double digit growth

CSL Behring issued their full-year report in August. They reported a 20% increase in revenue for Immunoglobulin, saying there is “significant patient demand in core indications.”

Grifols released their 3rd quarter financials in November, reporting 14.3% year to date growth in revenue from Immunoglobulin sales.

Takeda released their 2nd quarter financials in October, reporting 15.9% growth in revenue from Immunoglobulin sales. Takeda says there is “strong demand globally, especially in the U.S.”

Octapharma and Kedrion have not released their annual reports nor updated data yet.

Plasma collections are strong

CSL reported that “underlying fundamentals of plasma collection remain strong,” with ongoing plasma donation growth, and “continued reduction in CPL [Cost per liter].” They reported that their new Rika System was introduced in 84 centers, which they say can increase donation yield by around 10%.

Grifols’ 3rd quarter results similarly said their “Cost per liter continued to decline.”

Takeda is expecting to grow their U.S.-based plasma fleet by around another 10 centers this year, and has rolled out a personalized nomogram at 35 Biolife centers. As with the Rika system used by CSL, this is expected to allow for greater donation volume for each donation.

PEER-REVIEWED

Leni von Bonsdorff, Albert Farrugia, Fabio Candura, Peter O’Leary, Miguel A. Vesga, and Vincenzo De Angelis wrote a very helpful and interesting paper recently for Vox Sanguinis giving an overview of the plasma industry. The paper is entitled Securing commitment and control for the supply of plasma derivatives for public health systems. I: A short review of the global landscape.

Here’s the abstract:

The social market economies of the Western world considered the provision of plasma derivatives produced from publicly owned blood services as a legitimate state commitment and, until the last decades of the 20th century, many of the relevant jurisdictions maintained state-supported fractionation plants to convert publicly collected plasma into products for the public health system. This situation started to change in the 1990s, because of several converging factors, and currently, publicly owned/subsidized, not-for-profit fractionation activity has shrunk to a handful of players. However, the collection of plasma from publicly owned blood services has continued and recent developments have increased the interest of state authorities globally to increase the volume of plasma collected to increase the level of strategic independence in the supply of crucial plasma-derived medicines from commercial market pressures, particularly the global for-profit fractionation sector with its dominance of source plasma from paid donors in the United States. This paper reviews the development of the plasma industry and the evolution of the pressures on the supply of plasma, which has led to a situation of scarcity of key plasma-derived medicinal products (PDMPs).

That paper turns out to be Part I of a two-part series. The second part — by Albert Farrugia, Robert Perry, Françoise Rossi, Leni von Bonsdorff, Glynis Bowie, Jean-Claude Faber, Jeh-Han Omarjee, Jay Epstein, Jenny White — is entitled Generating pathways to domestically sourced plasma-derived medicinal products. This paper is similarly useful, especially since it discusses a subject we should spend more time discussing, namely, how to increase availability of plasma-derived medicinal products in low- and middle-income countries.

Tattoos are okay: In “New tatt? We're ok with that! Relaxing the tattoo deferral for plasmapheresis donors maintains safety and increases donations,” Claire E. Styles, Veronica C. Hoad, Robert Harley, John Kaldor and Iain B. Gosbell find that: “Allowing plasma donations immediately post-tattoo resulted in a substantial donation gain with no adverse safety effect.”

The study has had an immediate effect in Australia with Red Cross Lifeblood reducing the deferral period to only seven days if a donor received a tattoo at a properly licensed and regulated tattoo establishment.

NEWS

I spoke a few times with Amelia Wood from The Economist which led to a pair of articles about plasma published on August 29th.

The first (“The plasma trade is becoming ever-more hypocritical” ) tells us the current global situation and highlights the policy hypocrisy of too many countries, while the second (“People should be paid for blood plasma”) tells us that more countries should allow donor compensation. I agree with both of these arguments.

These two pieces update a series of articles The Economist published back in 2018 (America’s booming blood-plasma industry, Bans on paying for blood distort a vital global market, and, finally, Lift bans on paying for human blood plasma).

A lot has changed since 2018, and I think the articles in The Economist played a role in some of those changes, though the shortages that came in the wake of Covid played the bigger part. But one thing that hasn’t changed is that we are still not collecting enough plasma.

Here are a few other news items since July (if I’ve missed any, please let me know):

July 1: Kansas City Beacon discussed the ethics of plasma donation in The plasma you sell in east Kansas City could end up in medicine an ocean away:

Demand for plasma therapies is also up because more people are being diagnosed with diseases that could benefit from them.

For example, improved newborn screenings mean more people know they have primary immune deficiency, diseases that affect an estimated 500,000 people. But according to the Immune Deficiency Foundation, “tens of thousands” of others remain undiagnosed.

Only the United States, Germany, the Czech Republic and a few other countries allow payments for plasma donations. The countries that restrict payments have to rely on imports, primarily from the U.S. There is no synthetic alternative to human plasma.

July 6: ABC News’ Judd Boaz writes about Australia’s situation with plasma in As Australia's reliance on imported blood plasma grows, the ethics of paid donation are back in focus:

The commercial plasma industry has helped the United States become the largest supplier of plasma in the world, by far.

Despite making up just 4.2 per cent of the world's population, the United States accounts for around 70 per cent of all the source plasma in the world blood market, according to most analysts.

The country is so important to plasma supply that other countries have even directly sourced their plasma stateside.

After the outbreak of Mad cow disease in the late 90s, the UK shut down all plasma donations in the country and opened its own plasma collection company in the United States.

July 6: The Belgian Red Cross increased plasma donations significantly this year compared with last:

31,052 donors made 75,353 donations, or 13% more donations than in the first half of 2023. 5,143 people gave plasma for the first time, which is an increase of 73%. Often little is known exactly what plasma is used for. Among other things, transfusions are given to people in acute situations and people with blood diseases, or life-savening drugs are made.” In absolute numbers, Antwerp is the province with the most blood and plasma donations, but looked at the number of inhabitants, West Flanders has the highest share: 3.3% of the West Flemish are donors. The Flemish average is about 3%.” (Translated by Google)

August 12: RNZ in New Zealand discusses the issue of plasma for The Detail:

NZ Blood's transfusion medicine specialist, Dr Richard Charlewood says New Zealand is at a tipping point.

"Unless we can get our plasma donation numbers up we're going to get further and further behind. That's not good for us in a financial sense, in that we have to buy plasma from other countries, it's not good for us from a self sufficiency perspective.

September 10: Sabine El-Chidiac responds to Hamilton city council’s decision to declare itself a “paid plasma free zone” in Paid plasma should be welcomed in Ontario for the Hamilton Spectator:

Arguments made by Mayor Horwath and anti-paid plasma activists often centre on the morality of allowing people to commodify their bodies. But, strangely enough, they don’t have objections to Canada relying on the U.S. for plasma, where donors are paid.

November 16: CBC News covers Toronto city council’s decision to also declare itself a “paid plasma free zone.”

NEXT TIME

In the next Quarterly, I’ll go through some of the emerging public/private partnerships including the Grifols Egypt and Canadian Blood Services partnerships, and the new partnership between Uzbekistan and a Chinese company. We’ll also take a look at Indonesia’s partnership with a South Korean company which will see the construction of a fractionation facility in Indonesia.

UPDATES

November 18: Updated the data for U.S. centers in 2023, and European centers in 2022 and 2023. Added the “Next Time” section.

If I get booted from one plasma chain for low protein, can I donate at a different plasma chain if a number of years have passed? There are at least 10 clinics within walking distance of my apartment.